Common Sage Seeds - (Salvia officinalis)

- SKU:

- H1099

- Seed Count:

- Approx 50 seeds per pack

- Type:

- Perennial

- Days to Germination:

- 10-30 days at 65-75F

- Plant Spacing:

- 12-20"

- Light Preference:

- Full sun

- Soil Requirements:

- Well-drained

- Hardiness:

- Hardy - mulch heavily in cold climates below 10F

- Status:

- Heirloom, Non-Hybrid, Non-GMO seeds

Description

Common Sage - The Ancient Perennial Guardian

In 812 AD, growing this plant wasn't a choice; it was the law. When Charlemagne issued the Capitulary de Villis to manage the imperial estates, he didn't list Sage as a garnish—he listed it as a necessity. The ancients understood what modern gardeners often forget: Salvia officinalis is not just a seasoning for holiday poultry; it is a biological anchor. Emperors mandated it, and herbalists trusted it to secure the health of the household.

Details

To understand why Salvia officinalis is a drought-survivor, you have to look closely. Also known as Garden Sage, Common Sage, and Broadleaf Sage, this is a woody-stemmed,, semi-shrubby perennial in the mint family that grows 18-30 inches tall. It forms a bushy, sprawling mound of grey-green foliage that is oblong, finely veined, and pebbled in texture. That texture is functional, not just decorative; the leaves are covered in microscopic hairs that trap a boundary layer of moist air to reduce water loss.

Fragile glands filled with fat-soluble compounds like thujone, camphor, and cineole lie buried within that fuzz. These waxy oils lock in moisture, allowing the plant to thrive in the dry conditions of a Mediterranean hillside.

This variety thrives in Zones 4-8. In cool-summer gardens, it needs full sun - 6-8 hours - to fuel its oil production. In hot-summer climates - Zone 8b+, it appreciates afternoon shade to prevent the volatile oils from evaporating too quickly.

While often grown as a surface-feeder in pots, field-grown Sage sends taproots down to 39 inches. This expands the plant's rhizosphere—the active 'trading zone' where roots exchange sugars for biological moisture—deep into the subsoil. This deep access is why established plants can survive weeks without rain while surface crops wither.

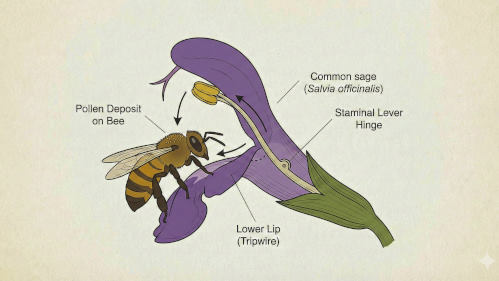

The flower is a masterpiece of biological engineering. As shown in the diagram, the blossom is equipped with a physical "staminal lever."

When a pollinator lands on the lower lip, which acts as the "tripwire" to seek nectar, a hinge swings down—thwack—depositing pollen specifically on the bee’s back, the one place it cannot groom. Because Sage is protandrous - meaning its male parts mature before the female parts do - nature designed this mechanism to ensure the bee carries that pollen to a different flower, guaranteeing genetic diversity.

History

Charlemagne valued it so highly that in 812 AD, he issued the Capitulary de Villis, a legislative act governing royal estates. In Chapter 70, he listed 73 mandatory plants for every imperial garden; he listed Salvia prominently. This decree effectively moved Sage from the wild hillsides to the monastery, ensuring its survival through the Dark Ages.

Perhaps its most famous legend is that of the "Four Thieves Vinegar." During the plague outbreaks of the Middle Ages, thieves who looted the dead credited their immunity to a vinegar infused with sage, rosemary, and other aromatics. While we view this as folklore, modern science validates the antimicrobial potency of the essential oils they were extracting. The medieval proverb "Cur moriatur homo cui Salvia crescit in horto?” ("Why should a man die whilst sage grows in his garden?") was not a poetic exaggeration; it was the medical consensus of the time.

Uses

In the Kitchen: The chemistry that protects the plant in the garden dictates how you use it in the kitchen. Because the essential oils are fat-soluble, do not boil raw Sage in water—unless specifically making tea—because the flavor will refuse to bind.

- Technique: To use Sage in soups or stews, you must "bloom" it first. Fry the leaves in the fat base with your onions and garlic, or sizzle them in brown butter to finish the dish. This heat transfers the essence from the leaf to the fat, which then carries the flavor through the broth.

- Pairings: This fat-loving nature makes it the classic pair for rich meats like pork, duck, and sausage, where the compounds physically help emulsify fats during digestion. However, that same sharpness provides a necessary "backbone" to vegetarian dishes. Try it minced and toasted over roasted butternut squash, sweet potatoes, or tomato soup.

- Chef's Preservation: To preserve the texture and flavor for months, fry fresh leaves in oil until crisp and store them in an airtight container.

The Apothecary: Beyond the kitchen, Sage has been the "storehouse" (officina) of herbalists for centuries.

- "Thinker's Tea": Historically, an infusion of sage leaves was drunk to combat grief and depression, earning it the nickname "Thinker's Tea" for its ability to enhance concentration and mental tone.

- Antiseptic Mouthwash: The leaves are rich in astringent tannins and volatile oils that soothe sore throats and gums.

- Recipe: Steep one teaspoon of fresh leaves in a cup of almost-boiling water for four minutes (covered). Swirl in a quarter-teaspoon of sea salt and a teaspoon of cider vinegar (or lime juice, as used by Jamaican herbalists). Swish while hot for one minute.

The flowers are edible, carrying a milder, nectar-sweet version of the leaf's flavor. Sprinkle them fresh on salads for color.

Companion Planting

Beneficial Pairings: Sage is the "Bouncer" of the garden. Its strong scent confuses pests that hunt by smell.

It masks Cabbage, Kale, and Broccoli from the Cabbage Moth. It repels the Carrot Rust Fly, confusing the fly before it can lay eggs.

Uniquely, Sage attracts the Wool Carder Bee, a species now naturalized across North America. Unlike passive honeybees, the male Wool Carder is territorial and will aggressively "body-check" other insects to defend his Sage patch. Planting Sage is effectively hiring security.

Antagonistic Pairings: Sage is a biological engineer that uses allelopathy - biological chemistry - to defend its space. It releases volatile compounds through its roots and leaf litter that can suppress the germination of neighbors.

Avoid: Planting near Cucumbers, Onions, or Fennel. The strong compounds can stunt their growth and inhibit flavor development. Give Sage its own territory.

Planting and Growing Tips

Sage does not want the moist environment of a vegetable bed. It needs a living, biologically active loam with sharp drainage and high mineral content. Avoid heavy nitrogen fertilizers, which act like cheap fuel—producing fast, floppy growth with diluted flavor.

Sow seeds indoors 6-8 weeks before the last frost, or direct sow once the soil has warmed to 60°F. Space plants at least 18-24 inches apart. A mature Sage plant requires airflow to prevent mildew. Once established, this plant is a master of conservation. Water deeply but infrequently to encourage the taproot to dive. If the soil stays wet, the plant will fail due to root rot.

Harvest Tips

Harvest in the morning (6:00 AM - 11:00 AM) after the dew has dried but before the sun hits peak heat. This is when the volatile oil content is highest. For the first year, harvest lightly by pinching the tips to encourage the plant to bush out. By year two, you can harvest continuously.

Sage is one of the few herbs that holds its character when dried. Hang bundles in a cool, dark place.

Learn More

From the soil to the seed to the food you eat - we'll help you grow your best garden!